We have a special place in our hearts for the trailblazers on Wall Street — the Merrill Lynch settlement was a big win for them. Bloomberg Business Week just published an in-depth breakdown on the suit and how it was settled:

It’s important to note that Merrill Lynch has a history of discriminating against employees of color:

In 1974 the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission sued Merrill, then the biggest brokerage, over race and sex discrimination. The firm, which admitted no fault, settled and entered a consent decree promising to increase the hiring of black brokers from a little more than 1 percent of the workforce to 6.5 percent. Merrill still hadn’t met this goal when the pact expired in 1995.

George McReynolds was one of the few and it was his unwillingness to accept being treated as “less than equal” that spurred the suit that is the subject of this story:

Over the years at Merrill—he started there in 1983— George McReynolds had gotten used to inequities small and large. With only a few fellow black brokers in the Nashville office, he felt isolated. Often excluded from work social events, he took to eating lunch at his desk; if he was out, he says, the receptionist sometimes told callers he didn’t work there. He also noticed that the other African American financial advisers at Merrill were rarely top producers—meaning they generated less business than their white colleagues—though they seemed to work as hard as everybody else.

In 2001 his manager asked him to team up with two younger white brokers, pooling their accounts and splitting the profits. The bulk of the combined accounts came from McReynolds. Right away the three had problems. “We didn’t agree on how business should be done,” he says. After two years the team broke up, and the office manager gave a majority of the accounts to the younger brokers. McReynolds says he lost $40 million in client assets and had to give up his office. His new desk was in a carrel outside the ladies’ restroom. “In this business, assets equal income,” McReynolds says. “It cut my income in half.”

The incident made him consider suing Merrill, but he worried he’d never prevail in court. (Merrill says numerous factors could determine how the accounts were divvied up after so long.) Then, in the spring of 2004, an arbitration panel found Merrill had systemically discriminated against female brokers and awarded $2.2 million to a single employee. At the time, women were a third of managers and executives in finance. African Americans made up 4 percent. In 2004, Merrill had almost 10,000 full brokers, not including trainees; fewer than 150 were black.

Really heartbreaking to read McReynolds experience, but after comparing notes with other black brokers across the firm he found he wasn’t alone.

In 2005, a Dallas-based broker named Maroc Howard and McReynolds hired Chicago-based Stowell & Friedman, the firm that had represented the women against Merrill in the ’90s. Stowell & Friedman took the racial-discrimination case on contingency and footed the upfront costs. Ultimately, 15 other brokers joined the suit. The plaintiffs asked the court to recognize a class of black brokers and trainees who worked at the firm from 2001 to 2006. As with most class actions, the biggest hurdle would be getting the judge to agree they had enough in common to be certified as a class. After that happens, financial expediency and exhaustion drive almost all cases toward settlements

Not long after the suit was filed the firm jumped into action defending themselves against the claims.

Merrill reacted swiftly. While it denied the claims made by McReynolds and his team, it did announce changes at the brokerages. The firm created new minority recruitment incentives, added an Office of Diversity to the duties of the unit’s operating chief, and went on a hiring spree that, for a period, more than doubled the number of black financial advisers. (Not many of the new hires stuck around; the attrition rate of black brokers remains high.) O’Neal met with the plaintiffs in New York, and McReynolds got his office back. Among co-workers, though, McReynolds found the response “chilly.” At the Christmas party, only a black sales assistant and a black couple who’d retired would talk to him. “After seeing the way Merrill Lynch treated me and other African Americans, two of my children told me they would never work for a place like Merrill Lynch,” McReynolds wrote in court documents. “A third child who has an MBA was told she was not qualified, even though a colleague’s son without a college degree was hired.”

Imagine how difficult it must be to work at the place you have filed a lawsuit against. We applaud the strength of these workers.

Merrill spent $12 million on a team of 8 experts who argued that society, not the firm, was at fault for the inequality and that wealth is primarily in the hands of white people who would rather work with white brokers, meanwhile lawyers for the black brokers prepared a much different argument on their much smaller budget.

The plaintiffs’ two experts, who charged a combined $1.6 million, argued that Merrill’s policies didn’t just replicate societal realities—they made them worse. They found that black brokers were far less likely to be asked to join teams than white brokers, which in turn limited the size of their books. The experts calculated that this alone accounted for as much as 28 percent of the wage gap.

They also found that, beginning in the first month of the training program for new hires, the company gave more and larger accounts from new customers or retiring brokers to the white trainees. (Merrill disputed their methodology.) That disparity was compounded by a seemingly meritocratic Merrill policy that rewarded higher producers by giving them even more accounts. “Even if all you did was give [white brokers] an advantage in Month One, blacks would always fall behind,” says Linda Friedman, a lead attorney for the plaintiffs.

Sounds a lot like the same kind of “white privilege” that has continued to help keep wealthy whites financially sound for generations.

The case almost hit a permanent roadblock in August 2010 when Federal District Judge Robert Gettleman ruled that the brokers didn’t have enough in common to be called a class. The group appealed and when the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals agreed to hear the case their lawyer was ready:

Friedman drew on a trick she’d learned over years of working on civil rights cases. White people, even judges, sometimes seemed to understand gender discrimination better than racial bias, so she likened Merrill’s teaming policy to when police departments first allowed women into the force. If departments allowed veteran officers to pick their own partners, the force would never have been integrated, she reasoned. This, Friedman argued, is what was happening to black brokers at Merrill. Judge Richard Posner, one of the leading conservative jurists in the country, pounced on the analogy, posing a series of additional questions. “Is it like a fraternity? They’re not picked?” he asked.

“When Judge Posner related it to a fraternity, we felt somebody finally got what we were trying to say,” McReynolds says. “It wasn’t clear that he would rule our way, but at least he understood our perspective.”

About a month after the hearing, Posner and the two other judges ruled in McReynolds’s favor, ordering the district judge to certify the class. Posner wasn’t saying that Merrill did discriminate—that’s something that would be argued in trial—but that the brokers did face companywide policies. Citing the example of female police officers, Posner wrote that the teaming policy could set off a “vicious cycle” where black brokers aren’t chosen for teams, so they earn less, so they don’t get as many accounts given to them, which in turn makes them less likely to be put on teams in the future. Friedman says the decision was the first time a judge certified a racial class against a financial firm, where the certification was not itself part of a settlement.

A trial was scheduled for early 2014, but by the summer of 2013, Merrill agreed to settle. The firm denied any wrongdoing but said it would pay $160 million, the largest cash award ever in a racial-discrimination employment case. Stowell & Friedman has asked for 21 percent of the pool; the rest will be split up among the more than 1,400 black brokers employed from 2001 to September 2013. The class representatives, 17 named plaintiffs, will each get a $250,000 bonus for their involvement in the case. How much each plaintiff gets will be determined by an independent monitor, but given McReynolds’s tenure, it’s not hard to imagine that his take could approach $1 million.

Merrill also agreed to three years of policy changes. The firm won’t distribute accounts to trainees in their first year and will place extra emphasis on the clients trainees bring in on their own. Merrill will hire two coaches to work with black brokers and two experts, one chosen by the plaintiffs and one by Merrill, to study the impact of team selection. Finally, all the settlement efforts will be overseen by a council of black brokers. “This is a very positive resolution of a lawsuit filed in 2005,” Merrill Lynch spokesman Bill Halldin said in a statement. “These new initiatives, developed in partnership with African American financial advisers and their legal team, will enhance opportunities for financial advisers in the future.” McReynolds will be on the committee in the first year. Similar changes implemented at Coca-Cola (KO), after it settled a 2000 bias suit, helped make it a diversity leader. Among the soda maker’s employees today is McReynolds’s oldest daughter, Jennifer.

This is far from happily ever after but it’s a huge step in the right direction. Settlements like this go a long way in holding corporations accountable. Kudos to McReynolds, Howard and the rest of their class for their bravery and commitment to this case.

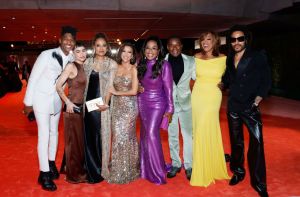

Photo Courtesy George McReynolds

Comments

Bossip Comment Policy

Please read our Comment Policy before commenting.