Rashida Jones Sister Kidada Says She Was Able To Pass For White When They Were Kids

Rashida Jones’ Sister Kidada Agrees “She Passed For White” But Did The Mean Girls At Harvard Scare Her Away From Dating Black Men Forever?

We got such strong reactions from our post about Rashida Jones picking her white side to make it in Hollyweird that we felt compelled to do a little digging into her old interviews and we had to revisit this 2005 Glamour Magazine interview that really delved into Rashida’s upbringing alongside her sister Kidad and includes quotes from their actress mom Peggy Lipton and their producer dad Quincy Jones.

It goes a long way in explaining why Rashida relates so well to Jewish folk and how she got turned off black men. We thought it was also interesting because her sister Kidada, who relates more to her black side, even says at one point that Rashida passed for white back in the day.

Here’s some excerpts from the part of the interview about their childhood, we’ve bolded the parts of the interview that stood out most to us:

RASHIDA: I wouldn’t trade my family for anything. My mother shocked her Jewish parents by marrying out of her religion and race. And my father: growing up poor and black, buckling the odds and becoming so successful, having the attitude of “I love this woman! We’re going to have babies and to hell with anyone who doesn’t like it!”

KIDADA: We had a sweet, encapsulated family. We were our own little world. But there’s the warmth of love inside a family, and then there’s the outside world. When I was born in 1974, there were almost no other biracial families–or black families–in our neighborhood. I was brown-skinned with short, curly hair. Mommy would take me out in my stroller and people would say, “What a beautiful baby…whose is it?” Rashida came along in 1976. She had straight hair and lighter skin. My eyes were brown; hers were green. IN preschool, our mother enrolled us in the Buckley School, an exclusive private school. It was almost all white.

RASHIDA: In reaction to all that differentess, Kidada tried hard to define herself as a unique person by becoming a real tomboy.

KIDADA: While Rashida wore girly dresses, I loved my Mr. T dolls and my Jaws T-shirt. But seeing the straight hair like the other girls had, like my sister had…I felt: “It’s not fair! I want that hair!”

PEGGY: I was the besotted mother of two beautiful daughters I’d had with the man I loved–I saw Kidada through those eyes. I thought she had the most gorgeous hair–those curly, curly ringlets. I still think so!

KIDADA: One day a little blond classmate just out and called me “Chocolate bar.” I shot back: “Vanilla!”

QUINCY: I felt deeply for Kidada; I thought racism would be over by the eighties. My role was to put things in perspective for her, project optimism, imply that things were better than they’d been for me growing up on the south side of Chicago in the 1930s.

KIDADA: I had another hurdle as a kid: I was dyslexic. I was held back in second grade. I flunked algebra three times. The hair, the skin, the frustration with schoolwork: It was all part of the shake. I was a strong-willed, quirky child–mischievous.

RASHIDA: Kidada was cool. I was a dork. I had a serious case of worship for my big sister. She was so strong, so popular, so rebellious. Here’s the difference in our charisma: When I was 8 and Kidada was 10, we tried to get invited into the audience of our favorite TV shows. Mine was Not Necessarily the News, a mock news show, and hers was Punky Brewster, about a spunky orphan. I went by the book, writing a fan letter–and I got back a form letter. Kidada called the show, used her charm, wouldn’t take no for an answer. Within a week she was invited to the set!

KIDADA: I was kicked out of Buckley in second grade for behavior problems. I didn’t want my mother to come to my new school. If kids saw her, it would be: “your mom’s white!” I told Mom she couldn’t pick me up; she had to wait down the street in her car. Did Rashida have that problem? No! She passed for white.

RASHIDA: “Passed”?! I had no control over how I looked. This is my natural hair, these are my natural eyes! I’ve never tried to be anything that I’m not. Today I feel guilty, knowing that because of the way our genes tumbled out, Kidada had to go through pain I didn’t have to endure. Loving her so much, I’m sad that I’ll never share that experience with her.

KIDADA: Let me make this clear: My feelings about my looks were never “in comparison to” Rashida. It was the white girls in class that I compared myself to. Racial issues didn’t exist at home. Our parents weren’t black and white; they were Mommy and Daddy.

RASHIDA: But it was different with our grandparents. Our dad’s father died before we were born. We didn’t see our dad’s mother often. I felt comfortable with Mommy’s parents, who’d come to love my dad like a son. Kidada wasn’t so comfortable with them. I felt Jewish; Kidada didn’t.KIDADA: I knew Mommy’s parents were upset at first when she married a black man, and though they did the best they could, I picked up on what I thought was their subtle disapproval of me. Mommy says they loved me, but I felt estranged from them.

While Rashida stayed and excelled at Buckley, Kidada bumped from school to school; she got expelled from 10 in all because of behavior problems, which turned out to be related to her dyslexia.

KIDADA: We had a nanny, Anna, from El Salvador. I couldn’t get away with stuff with her. Mommy knew Anna could give her the backup she needed in the discipline department because she was my color. Anna was my “ethnic mama.”

PEGGY: Kidada never wanted to be white. She spoke with a little…twist in her language. She had ‘tude. Rashida spoke more primly, and her identity touched all bases. She’d announce, “I’m going to be the first female, black, Jewish president of the U.S.!”

KIDADA: When I was 11, a white girlfriend and I were going to meet up with these boys she knew. I’d told her, because I wanted to be accepted, “Tell them I’m tan.” When we met them, the one she was setting me up with said, “You didn’t tell me she was black.” That’s When I started defining myself as black, period. Why fight it? Everyone wanted to put me in a box. On passports, at doctor’s offices, when I changed schools, there were boxes to check: Caucasian, Black, Hispanic, Asian. I don’t mean any dishonor to my mother–who is the most wonderful mother in the world, and we are so alike–but: I am black. Rashida answers questions about “what” she is differently. She uses all the adjectives: black, white, Jewish.

RASHIDA: Yes, I do. And I get: “But you look so white!” “You’re not black!” I want to say: “Do you know how hurtful that is to somebody who identifies so strongly with half of who she is?” Still, that’s not as bad as when people don’t know. A year ago a taxi driver said to me, That Jennifer Lopez is a beautiful woman. Thank God she left that disgusting black man, Puffy.” I said, “I’m black.” He tried to smooth it over. IF you’re obviously black, white people watch their tongues, but with me they think they can say anything. When people don’t know “what” you are, you get your heart broken daily.

KIDADA: Rashida has it harder than I do: She can feel rejection from both parties.

RASHIDA: When I audition for white roles, I’m told I’m “too exotic.” When I go up for black roles, I’m told I’m “too light.” I’ve lost a lot of jobs, looking the way I do.

PEGGY: As Kidada grew older, it became clear that she wouldn’t be comfortable unless she was around kids who looked more like her. So I searched for a private school that had a good proportion of black students, and when she was 12, I found one.

KIDADA: That changed everything. I’d go to my black girlfriends’ houses and–I wanted their life! I lived in a gated house in a gated neighborhood, where playdates were: “My security will call your security.” Going to my black friends’ houses, I saw a world that was warm and real, where families sat down for dinner together. At our house, Rashida and I often ate dinner on trays, watching TV in Anna’s room, because our dada was composing and performing at night and Mom sat in on his sessions.

RASHIDA: But any family, from any background, can have that coziness too.

KIDADA: I’m sure that’s true, but I experienced all that heart and soul in black families. I started putting pressure on Mommy to let me go to a mostly black public school. I was on her and on her and on her. I wouldn’t let up until she said yes.

PEGGY: So one day when Kidada was 14, we drove to Fairfax High, where I gave a fake address and enrolled her.

KIDADA: All those kids! A deejay in the quad at lunch! Bus passes! All those cute black boys; no offense, but I thought white boys were boring. I fit in right away; the kids had my outgoing vibe. My skin and hair had been inconveniences at my other schools–I could never get those Madonna spiked bangs that all the white girls were wearing–but my girlfriends at Fairfax thought my skin was beautiful, and they loved to put their hands in my hair and braid it. The kids knew who my dad was an my stock went up. I felt secure. I was home.

RASHIDA: Our parents divorced when I was 10; Kidada went to live with Dad in his new house in Bel Air, and I moved with Mom to a house in Brentwood. Mom was very depressed after the divorce, and I made it my business to keep her company.

KIDADA: I wanted to live with Dad not because he was the black parent, but because he traveled. I could get away with more.

RASHIDA: At this time, anyone looking at Kidada and me would have seen two very different girls. I wore my navy blue jumper and crisp white blouse; K wore baggy Adidas sweatsuits and door-knocker earrings. My life was school, school, school. I’m with Bill Cosby: It’s every bit as black as it is white to be a nerd with a book in your hand.

KIDADA: The fact that Rashida was good at school while I was dyslexic intimidated me and pushed me more into my defiant role. I was ditching classes and going to clubs.

RASHIDA: About this time, Kidada was replacing me with younger girls from Fairfax who she could lead and be friends with.

KIDADA: They were my little sisters, as far as I was concerned.

RASHIDA: When I’d go to our dad’s house on weekends, eager to see Kidada, the new “little sisters” would be there. She’d be dressing them up like dolls. It hurt! I was jealous!

KIDADA: You felt that? I always thought you’d rejected me.

RASHIDA: Still, our love for the same music–Prince, Bobby Brown, Bell Biv DeVoe–would bring us together on weekends.

It sounds like the Jones girls had quite an interesting upbringing, but it’s clear that Kidada always knew she was attracted to black men and Rashida was more open to “others.” Still, we thought it interesting that Rashida says she never tried to be what she wasn’t but later in the story she describes how once she went to college at Harvard she “chose” her black side and created an identity to “fit in” with the black crowd there.

Hit the flip for that and to see actual scans from the story.

KIDADA: After I graduated from high school, I found my passion: trend forecasting. I enrolled at L.A.’s Fashion Institute of Design and Merchandising, and my academic problems went out the window. All it took was finding something I loved for me to get A’s! While I was there, designer Tommy Hilfiger noticed a cover of Vibe magazine I had styled. He offered me a job in New York, being his muse, and he left me work in every part of his company–designing, marketing, advertising, modeling. Tommy got urban music. I was working with the hottest hip-hop acts: TLC, Snoop Dogg, Usher.

RASHIDA: And finally I was leaving for college, for Harvard. Daddy would have died if I turned Harvard down. Harvard was supposed to be the most enlightened place in America, but that’s where I encountered something I’d never found in L.A.: segregation. The way the clubs and the social life were set up, I had to choose one thing to be: black or white. I chose black. I went to black frat parties and joined the Black Student Association, a political and social group. I protested the heinous book The Bell Curve [which claims that a key determinant of intelligence is ethnicity], holding a sign and chanting. But at other protests–on issues I didn’t agree with– wondered: Am I doing this because I’m afraid the black students are going to hate me if I don’t? As a black person at Harvard, the lighter you were, the blacker you had to act. I tried hard to be accepted by the girls who were the gatekeepers to Harvard’s black community. One day I joined them as usual at their cafeteria table. I said, “Hey!”–real friendly. Silence. I remember chewing my food in that dead, ominous silence. Finally, one girl spoke. She accused me of hitting on one of their boyfriends over the weekend. It was untrue, but I think what was really eating her was that she thought I was trying to take away a smart, good-looking black man–and being light-skinned, I wasn’t “allowed” to do that. I was hurt, angry. I called Kidada in New York crying. She said, “Tell her what you feel!” So I called the girl and…I really ripped her a new one. But after that, I felt insidious intimidation from that group. The next year there was a black guy I really liked, but I didn’t have the courage to pursue him. Sometimes I think of him and how different my life might be if I hadn’t been so chicken. The experience was shattering. Confused and identity-less, I spent sophomore year crying at night and sleeping all day. Mom said, “Do you want to come home?” I said, “No.” Toughing it out when you don’t fit in: That was the strength my sister gave me.

RASHIDA: Fortunately, I’d gotten interested in acting, and my theater classes roused me from my depression. I also made new friends: I had a Jewish boyfriend, with whom I got into my own Jewishness, I had black friends who weren’t in that clique. I had theater friends, gay friends, rave friends. I realized: I’m a floater. I float among groups. If Kidada defined herself as black at 11, I defined myself as multiracial at Harvard.

RASHIDA: After graduating from Harvard, my college boyfriend and I broke up, and I moved to New York to be an actress. Getting into the business was so much harder than I expected–almost soul-destroying. Then I met a young [white] actor who seemed to know what he was doing, and I moved to L.A. to be with him, not realizing that I was glomming on to him for my sense of identity. But I was happy about relocating, because Kidada was back in L.A. too. During my four years at Harvard, K and I had kept up by calling each other and spending some weekends together, trying to translate our love for each other into a relationship that didn’t have tugs and thorns in it.

KIDADA: Rashida said to me: Come hang with my friends. Try something different! I thought: This will be fun…

RASHIDA: But instead of bonding with Kidada, I rejected her–not because I wanted to, but because my boyfriend was telling me not to be dominated by my older sister. My boyfriend didn’t want me to be at Kidada’s 25th birthday party, so I skipped it. When I called her to apologize, she was so beyond anger, she murmured, “Whatever.”

KIDADA: That hurt. A lot. But I had Aaliyah.

RASHIDA: In 2000, I joined the cast of Boston Public. I also broke off that negative, unhappy relationship. I started a long-distance romance with a deejay who was white and Jewish but is knowledgeable about urban music–like me, a floater. After I moved back to NY, we got engaged.

It sounds like Rashida has allowed herself to be dominated a lot in life period — by her sister, her boyfriend and the kids at school. Do you think that her “less black” appearance has actually hindered her in a sense because she’s become less confident about her own identity?

It’s interesting that she notes how different her life would have been if she would have pursued the black guy she liked in college. Do you think she’s decided it’s too late at this point?

WENN

Continue Slideshow

-

Frames Per Second Podcast: Zendaya, Timothée Chalamet & More — Who’s The Future of Hollywood?

-

'Palm Royale' Exclusive: Amber Chardae Robinson On Playing Black Feminist In Series Set In 1969, 'Not Much Has Changed For Women'

-

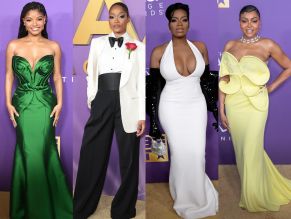

Who Looked More Bangin'? The Best Dressed Looks From The 2024 NAACP Image Awards Red Carpet

-

Megan Thee Stallion Presents At Crunchyroll Anime Awards 2024, Stuns In Skintight Leather 'JoJo's Bizarre Adventure' Look

-

Checks Over Stripes? Kanye West Spotted In Nike At Milan Fashion Week

-

Texas Hold 'Em: 6 Times Beyoncé Reminded Us She's A Country Queen

-

Bad & Boujee: Our Hollywood Faves Dripped Decadently For The Academy Museum Gala

-

Balenci Bardi: Cardi B Makes Her Debut On The Catwalk For Balenciaga Fall '24 Show

Comments

Bossip Comment Policy

Please read our Comment Policy before commenting.